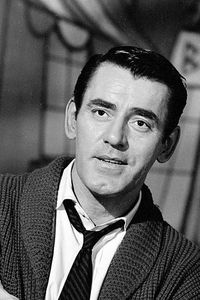

Edward Dmytryk was born in San Francisco to Ukrainian immigrant parents. His childhood was marked by tragedy when his mother passed away when he was just six years old, leaving his father, a strict disciplinarian, to raise him. The young boy was frequently beaten by his father, leading him to start running away from home in his early teens.

As a result, juvenile authorities stepped in and allowed Edward to live alone at the age of 15, finding him part-time work as a film studio messenger. Despite this difficult start, Edward was an outstanding student in physics and mathematics, earning a scholarship to the California Institute of Technology.

However, he dropped out of college after just one year to pursue a career in the film industry, eventually working his way up from film editor to director. By the late 1940s, he had established himself as one of Hollywood's rising young directing talents.

Tragedy struck again when Edward's career was interrupted by the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC),a congressional committee that aimed to root out and destroy alleged Communist influence in Hollywood. As a lifelong political leftist who had briefly been a Communist Party member during World War II, Edward was one of the so-called "Hollywood Ten" who refused to cooperate with HUAC.

As a result, he was thrown in prison for refusing to cooperate, and after several months behind bars, Edward decided to cooperate with the committee, testifying against his former colleagues and giving the names of people he claimed were Communists. Many in the Hollywood community never forgave him for this betrayal, and it overshadowed his career for the rest of his life.

In the 1970s, Edward's directing career began to stall, and he decided to return to academic life, this time as a teacher. He went on to become a professor of film theory and production at the University of Texas at Austin and later a chair in filmmaking at the University of Southern California.

During his teaching career, Edward also authored several books on various aspects of filmmaking, as well as two volumes of memoirs. He continued to teach and write until his death, leaving behind a legacy that was both complex and controversial.