Here is the biography of George Stevens:

George Stevens was born on December 18, 1904, in Oakland, California, to actor Landers Stevens and his wife, actress Georgie Cooper. His parents' theatrical company performed in the San Francisco Bay area, and as individual performers they also toured the West Coast as vaudevillians on the Opheum circuit. Their theatrical repertoire included the classics, giving the young George the chance to forge an understanding of dramatic structure and what works with an audience.

Stevens' movie adaptation of "I Remember Mama," the chronicle of a Norwegian immigrant family trying to assimilate in San Francisco circa 1910, could be a mirror on the Stevens family's own move to Los Angeles circa 1922. In "Mama", the members of the Hanson family feel like outsiders, a theme that resonates throughout Stevens' work. Acting was considered an insalubrious profession before the rise of Ronald Reagan's generation of actors into the halls of power, and being a member of an acting family necessarily marked one as an outsider in the first half of the 20th century. Young George had to drop out of high school to drive his father to his acting auditions, which would have further enhanced his sense of being an outsider.

Stevens learned the art of visual storytelling while working as an assistant cameraman at the Hal Roach Studios, where he was part of a team that shot low-budget westerns, some of which featured Rex. Within two years, Stevens became a director of photography and a writer of gags for Roach on the comedies of Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy.

His first credited work as a cameraman at the Roach Studios was for the Stan Laurel short "Roughest Africa" (1923). Stevens was a terrific cameraman, most notably in Laurel & Hardy's comedies (both silent and talkies),and it was as a cameraman that his aesthetic began to develop. The cinema of George Stevens was rooted in humanism, and he focused on telling details and behavior that elucidated character and relationships. This aesthetic started developing on the Laurel & Hardy comedies, where he learned about the interplay of relationships between "the one who is looked at" and "the one doing the looking."

Stevens' first classic was the sixth Astaire-Rogers musical, "Swing Time" (1936). Stevens' past as a lighting cameraman prepared him for the innovative visuals of this musical comedy. Through his control of the camera's field of vision, Stevens as a director creates an atmosphere that engenders emotional effects in his audience. In one scene, Astaire opens a mirrored door that the scene's reflection in actuality is being shot on, and being keyed into the illusion emotionally introduces the audience into the picture, in sly counterpoint to Buster Keaton's walk into the screen in his "Sherlock, Jr." (1924). Stevens' use of light in "Swing Time" is audacious. He freely introduces light into scenes, with the effect that it enlivens them and gives them a "light" touch, such as the final scene where "sunlight" breaks out over the painted backdrop.

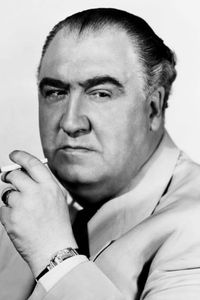

Stevens' next classic was the rip-roaring adventure yarn "Gunga Din" (1939),based on the Rudyard Kipling poem. Though no longer politically correct in the 21st century, the picture still works in terms of action and star power, as three British sergeants--Cary Grant, Victor McLaglen, and Douglas Fairbanks Jr.--try to put down a rampage by a notorious death cult in 19th-century colonial India.

Having learned his craft in the improvisational milieu of silent pictures, Stevens would often wing it, shooting from an underdeveloped screenplay that was ever in flux, finding the film as he shot it and later edited it. With filmmaking becoming more and more expensive in the 1930s due to the studios' penchant for making movies on a vast scale than they had previously, Stevens' methods led to anxiety for the bean-counters in RKO's headquarters. His improvisatory crafting of "Gunga Din" resulted in the film's shooting schedule almost doubling from 64 to 124 days, with its cost reaching a then-incredible $2 million (few sound films had grossed more than $5 million up to that point, and a picture needed to gross from two to 2-1/2 times its negative cost to break even).

Stevens' theme of the outsider continued with his next classic, "Shane" (1953). The eponymous gunman is an outsider, but so is the Starrett family he has decided to defend, as are the "sodbusters", and even the range baron who is now outside his time, outside his community and outside human decency.

In a money-dominated culture in which the ethos "What Have You Done For Me Lately?" is prominent, George Stevens was relegated to has-been status