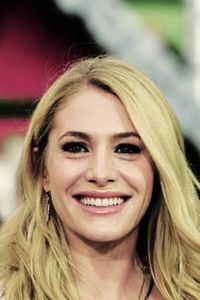

Kay Francis is a forgotten star from Hollywood's Golden Era. She was one of America's most popular actresses in the 1930s, earning the title "Queen of Warner Brothers." By 1935, she was earning a yearly salary of $115,000, compared to Bette Davis' $18,000. Kay was born to actress Katherine Clinton and businessman Joseph Gibbs. She did not start her career in show business, but instead sold real estate and arranged parties for wealthy socialites.

After her marriage to James Dwight Francis in 1922, Kay adopted his surname. Her first acting job was in a modernized version of "Hamlet" in 1925. She then appeared in several stage productions, including "Crime" and "Elmer the Great." Her stage work caught the attention of Paramount, and she was offered a contract in 1929.

Kay had a bit part in the first Marx Brothers film, "The Cocoanuts," and then began playing sophisticated seductresses opposite stars like William Powell and Ronald Colman. She appeared in the Lubitsch comedy "Trouble in Paradise" and the comedy/drama "One Way Passage." Paramount decided to let Kay move to Warner Brothers, where she would remain for the rest of the decade.

At Warner Brothers, Kay became known for her glamorous wardrobe and was dubbed Hollywood's "best dressed woman." She spent a lot of time and effort on collaborative efforts with costume designers to select the right clothes for the parts she played. By the mid-1930s, Kay was earning $5,250 per week and was voted Hollywood's sixth most popular star.

Kay had major hits with "I Found Stella Parish" and "Confession," both of which were excellent money-spinners for the studio. However, her falling out with the studio executives over her salary led to a lawsuit against Warner Brothers. The tight control the studio exercised over the roles she played on screen caused her to feel typecast in sentimental melodramas and biopics.

By the end of the decade, the "Queen of Warner Brothers" mantle had passed on to Bette Davis. Kay co-produced several B-movies as vehicles for herself at Monogram and made a brief return to stage work before retiring permanently in 1952. She spent the remainder of her life in virtual seclusion in New York and on Cape Cod.